Many species have arrived and vanished throughout Earth’s history. Unfortunately, many of these extinct species vanished long before humans ever set foot on the earth, despite the fact that some of them were amazing in and of themselves. These twenty extinct wild creatures were previously common on Earth.

1. Woolly Mammoth

During the Ice Age, there existed a massive, hairy animal like an elephant called the woolly mammoth. It was wrapped in a thick coat to keep out the cold and possessed long, curving tusks. The appearance and behaviour of this species are among the best studied of any prehistoric animal because of the discovery of frozen carcasses in Siberia and North America, as well as skeletons, teeth, stomach contents, dung, and depictions of life in prehistoric cave paintings. Mammoth remains had long been known in Asia before they became known to Europeans in the 17th century.

2. Saber-Toothed Tiger

Tar pits were a common and lethal feature of the terrain ten thousand years ago. Animals would become caught, sink into the asphalt, and perish. More than a million bones have been found by experts in the Californian tar pits of La Brea. Among the best-preserved and largest collections of sabertooth (Smilodon fatalis) bones in the world is this one. Scientists use information gathered from the La Brea tar pits to reconstruct the region’s natural history, which includes the history of the sabertooth cat. The sabertooth cat was first documented in the archaeological record two million years ago, according to scientists. Sabertooths, who are related to modern cats, inhabited a large portion of North and South America. But there are currently no known living descendants of the sabertooth cat.

3. Dodo

East of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean lies the island of Mauritius, home to the extinct flightless dodo (Raphus cucullatus). The nearest living relative of the dodo was the flightless and likewise extinct Rodrigues solitaire. Together, they constituted the subfamily Raphinae, a group of extinct birds without wings that belonged to the same family as doves and pigeons. The Nicobar pigeon is the dodo’s closest surviving relative.

4. Thylacine

The thylacine, which was once native to the Australian mainland as well as the islands of Tasmania and New Guinea, was a carnivorous marsupial. It is sometimes referred to as the Tasmanian wolf or Tasmanian tiger. Around 3,600–3,200 years ago, before the arrival of Europeans, the thylacine went extinct in mainland Australia and New Guinea. This could have been due to the introduction of the dingo, which never made it to Tasmania despite having the earliest known record from around the same time.

5. Megalodon,

Megalodon, also known as Otodus megalodon, is the common name for an extinct species of large mackerel shark that lived from the Early Miocene to the Pliocene epochs, roughly 23 to 3.6 million years ago (Mya). Reclassified into the extinct family Otodontidae, which separated from the great white shark during the Early Cretaceous, O. megalodon was previously believed to be a member of the Lamnidae and a close relative of the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).

6. Pterosaurs

The bodies and portions of the wings of pterosaurs were coated in pycnofibers, which are filaments that resembled hair. Pycnofibers could grow into feather branches or into simple filaments. These could be similar to the down feathers that are present on some non-avian dinosaurs as well as avian dinosaurs, indicating that early feathers may have evolved as insulation in the common ancestor of pterosaurs and dinosaurs. Pterosaurs would have possessed fluffy or silky coats in life, unlike the feathers of birds. These were energetic, warm-blooded (endothermic) creatures.

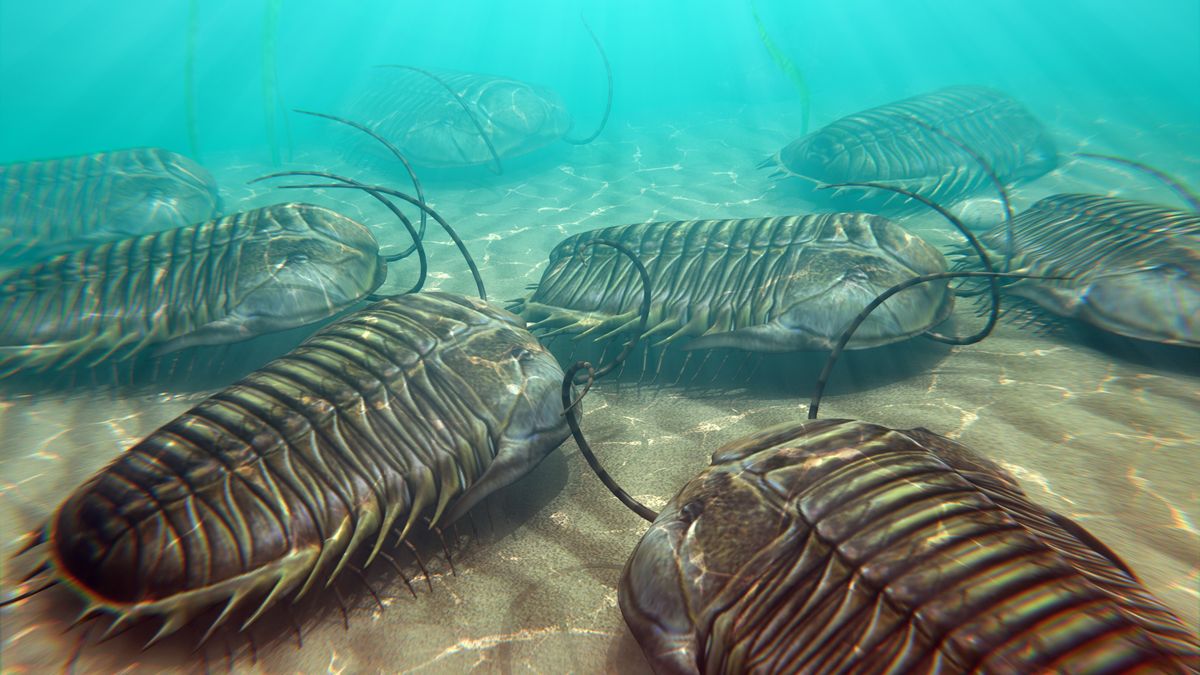

7. Trilobites

Trilobites have developed into a wide variety of ecological niches. Some of them swam and fed on plankton, while others roamed over the seabed as scavengers, predators, or filter feeders. On land, some even crawled. With the probable exception of parasitism, which is still up for scientific debate, trilobites exhibit the majority of the lifestyles predicted by contemporary marine arthropods. It is also believed that some trilobites, especially those in the family Olenidae, had a symbiotic association with bacteria that consumed sulfur, from which they obtained nourishment.

8. Quagga

It is estimated that the quagga measured 257 cm (8 feet 5 inches) in length and 125–135 cm (4 feet 1 inch–4 feet 5 inches) in height at the shoulders. Its restricted pattern of mostly brown and white stripes, which were mostly on the front of the body, set it apart from other zebras. The back was stripedless, brown, and gave the impression of being more equine. The individuals’ distribution of stripes differed significantly from one another. The quagga’s behavior is unknown; however, it may have been collected in herds of thirty to fifty individuals.

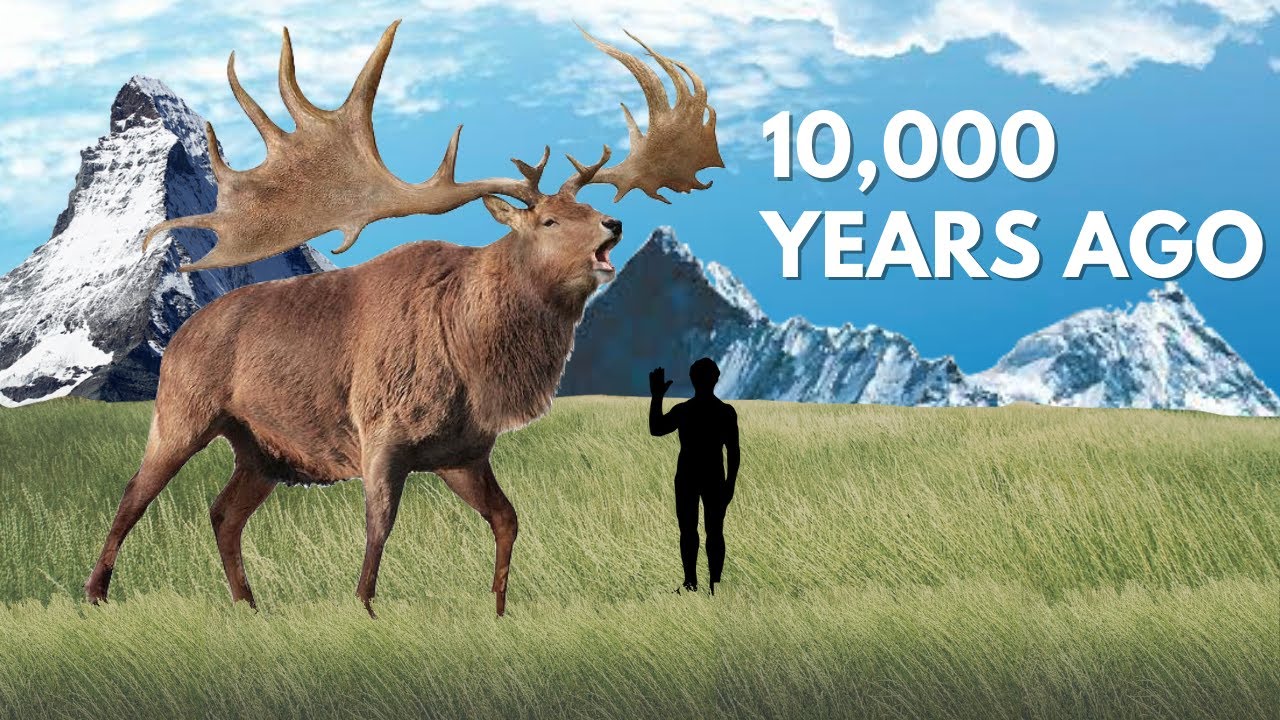

9. Irish Elk

One of the largest deer species ever to have existed is the Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus), also known as the enormous deer or Irish deer. It is an extinct species of deer in the genus Megaloceros. During the Pleistocene, its range stretched from Lake Baikal in Siberia to Ireland, where it is known from numerous bones discovered in bogs. The species’ most recent remains have been radiocarbon-dated to western Russia, some 7,700 years ago. Its antlers are the biggest known deer antlers, reaching a maximum diameter of 3.5 meters (11 feet).

10. Steller’s Sea Cow

Georg Wilhelm Steller wrote a description of the extinct Sirena gigas, or Steller’s sea cow, in 1741. Its range had stretched over the North Pacific during the Pleistocene era, and it had probably contracted to such an extreme degree because of the glacial cycle. At that time, it was only found in the vicinity of the Commander Islands in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Russia. It’s probable that the animal was in contact with native communities prior to the arrival of European settlers. When the crew of Vitus Bering’s Great Northern Expedition was shipwrecked on Bering Island, Steller first came upon it. A significant portion of our understanding of its behavior originates from Steller’s observations made on the island, which he chronicled in his posthumous book On the Beasts of the Sea.

11. Passenger Pigeon

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Passenger_pigeonAn extinct pigeon species that was native to North America was the passenger pigeon, also known as the wild pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius). Because of the species’ migratory tendencies, its common name is taken from the French term passager, which means “passing by.”. The migratory features are also mentioned in the scientific name. Although genetic investigation has revealed that the genus Patagioenas is more closely related to it than the Zenaida doves, it was long believed that the physically similar mourning dove (Zenaida macroura) was its closest relative.

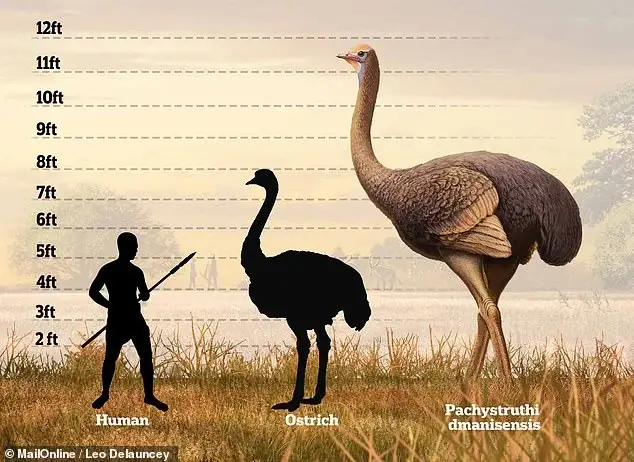

12. Moa

Although moa skeletons are typically rebuilt upright to generate an impressive height, examination of their spinal articulations suggests that they most likely held their heads forward, much like kiwis. The horizontal position was shown by the spine’s attachment to the back of the skull rather than the base. As a result, they would have been able to graze on low plants and, when needed, raise their heads to browse trees. As a result, the height of the larger moa has been reevaluated. Nonetheless, moa or moa-like birds (perhaps geese or adzebills) are seen with their necks upright in Māori rock art, suggesting that moa were more than capable of adopting both neck postures.

13. Great Auk

The flightless alcid species known as the big auk (Pinguinus impennis) went extinct in the middle of the 1800s. In the genus Pinguinus, it was the sole extant species. It is not closely related to the birds of the Southern Hemisphere that are now called penguins. The Europeans discovered these birds later, and sailors gave them the name “penguins” due to their morphological similarity to the great auk. Few great auk breeding grounds were available due to the rarity of rocky, isolated islands with easy access to the ocean and an abundant food supply.

14. Diprotodon

The largest known marsupial to have ever existed is Diprotodon, which is significantly larger than the nearest extant relatives, wombats and koalas. It belongs to the extinct Diprotodontidae family of herbivores, which also includes other huge quadrupedal animals. It developed to a maximum size of 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) at the shoulders and almost 4 m (13 ft) from head to tail. It was probably rather heavy, weighing up to 3,500 kg (7,700 lb). Males were considerably larger than females. Diprotodon, which occupied most of Australia, was able to traverse great distances by using its elephant-like legs for support. The wrists and ankles likely supported the majority of the weight since the digits were weak. The hindpaws had a 130° inward angle.

15. Glyptodon

Glyptodon is a genus of prehistoric large mammals that are related to modern armadillos. Fossils of these animals, which date from the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs (5.3 million to 11,700 years ago), have been discovered in deposits in North and South America. From head to tail, Glyptodon and its closely related glyptodonts were covered in a thick layer of armor that resembled a turtle’s shell but was made of bony plates similar to an armadillo’s. Just the body shell extended up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) in length. The tail, which was likewise armored, had the potential to be a deadly club. In fact, in certain Glyptodon cousins, the tail tip was a knob of bone that was occasionally spiky.

16. Megaloceros

Found mostly as fossils in Pleistocene deposits in Europe and Asia, the Irish elk (Megaloceros giganteus) is an extinct species of deer known for its enormous body size and huge antlers. The Pleistocene Epoch began 2.6 million years ago and ended approximately 11,700 years ago. Although the species was found all over Eurasia, Ireland had the highest concentration of it. The Irish elk is the largest known species of Megaloceros, though there are a few more. It resembled the contemporary moose (Alces alces) in size, and some of its specimens possessed the biggest antlers of any known deer species, measuring up to 4 meters (about 13 feet) in diameter.

17. Smilodon

The largest species of milodon, Smilodon populator, is most known for having relatively long canines, the longest of any saber-toothed cat species at around 28 cm (11 in). At a growth rate of 7 mm/month, those of S. fatalis took 18 months to achieve their maximum size. These teeth were sharply serrated and had thin canines. They couldn’t have bitten into bone since they were so delicate. As a result, the cats refrained from using their long teeth to sever their prey. They did not bite until they had subdued their prey.

18. Anomalocaris

Anomalocaris was an apex predator, even though it consumed much softer food, most likely worms and basic vertebrates. With its flexible lobes on the sides of its body, it waved itself through the water. The lobes on either side of the body functioned as a single “fin” to maximize swimming efficiency because each lobe slanted below the one more posterior to it. The development of a remote-controlled model demonstrated the fundamental stability of this swimming technique.

19. Titanoboa

It was the first era following the age of dinosaurs in a region of the planet that had just recovered from an epic-scale asteroid explosion. The tropical rainforests that are available today along the equator were create from blast.

There were plenty of hiding spots for Titanoboa in this lush, tropically foliaged, wet, and marshy environment. The largest snake in the world, Titanoboa, has captured our attention and opened a doorway into the world of the prehistoric past. In paleontology, it continues to be a topic of fascination and research, offering insights into past ecosystems and the evolutionary history of reptiles.

20. Archaeopteryx

Like Tyrannosaurus rex and Allosaurus, Archaeopteryx was a member of the theropod family and had a long, bony tail. However, it also possessed traits shared by contemporary birds, including feathers and a wishbone, or furcula, that facilitate flight. It had wings, too, albeit with claws. And Archaeopteryx might be able to fly. It is still up for debate among scientists whether Archaeopteryx was able to actually fly by lifting off the ground and flapping its wings, or if it was able to climb trees with its claws and then glide from branch to branch or down to the ground. Regarding those feathers, as well, there is proof that certain dinosaurs, such as the Velociraptor, possessed feathers on their bodies that were intended to keep them warm. But the feathers of the archaeopteryx are designed for flight.

Share this content:

+ There are no comments

Add yours